We find Shakespeare because Shakespeare is who we want to find.

In 2015 George Koppelman and Daniel Wechsler published a second edition of Shakespeare's Beehive, which was first released in April of 2014. The authors have added two chapters and updated the existing materials in support of their claim that their copy of John Baret's An Alvearie or Quadruple Dictionarie (1580) was annotated by William Shakespeare. I have previously written about the first edition in "Shakespeare's Beehive and Shakespeare's Printer." In that essay, my main focus was on the role played by the "lost years" story that Shakespeare got his start in London by working in the book trade -- a story that is cited by Koppelman and Wechsler. The research that provides the foundation for my previous critique of Shakespeare's Beehive can be found in my own book, Selling Shakespeare. If you are interested in the issues and problems raised by the stories we tell about Shakespeare, then I recommend you follow the links. In this essay, unless otherwise noted, I quote from the second edition, which I have purchased, read, and annotated.In a review of the first edition in the Times Literary Supplement, H. R. Woudhuysen -- a knowledgeable and respected expert on manuscript and print culture in early modern England -- wrote that "Shakespeare's Beehive raises many questions that don't really deserve detailed answers." Why write another review essay of this book, then? Why am I doing this?

First, as Shakespeareans have learned, ignoring amateur enthusiasts and conspiratorial eccentrics does not mean that their theories go away -- in fact they are often intensified when Shakespeare scholars refuse to engage with them. This is why a book like James Shapiro's Contested Will has been so important: it traces the origins of a particular controversy, while showing how scholars have been implicated in and helped create that controversy. My intention here is to take the arguments presented in the book seriously by subjecting them to a proper analysis and offering my own assessment as a scholar, drawing on two decades of training and study in Shakespeare, book history, and bibliography.

Second, I want to attend to the narrative and rhetorical strategies employed by Koppelman and Wechsler, particularly in the first part of their book in which they outline their evidence and make their case. Some of their methods and motivations differ only in degree, rather than in kind, from certain strands of mainstream scholarship. It can thus be used as a case study that demonstrates (if in an exaggerated way) some of the potential problems in contemporary Shakespeare studies. I want to emphasize that Shakespeare's Beehive is a narrative, because the authors try to shape and limit the responses of readers, who are continually prodded to arrive at the conclusion toward which they point. There is also a repeated insistence that no single detail clinches the case; rather, it is the totality of all the details, taken together, which proves their claim. Details still matter, though, and so I have attended closely some of the more important pieces of evidence.

After reading Shakespeare's Beehive cover-to-cover -- for the second time -- I will offer the following statements. I want to emphasize that these are strictly critical statements. This is not one of the "personal attacks on our intentions, methods, and qualifications" (361) that Koppelman and Wechsler fear. This is because scholarship and criticism is (or at least should be) impersonal. A critique of a work of scholarship is not a personal attack. This is just how scholarship works.

I am not convinced by the argument that this book presents. I find the methodology to be ineffective. There are countless mistakes and errors in interpretation. At times their analysis of the presented evidence is not consistent. I find the repeated circumlocutions, which try to indirectly imply their argument rather than stating it explicitly, to be both unnecessary and distracting, drawing attention away from the actual evidence presented. The "parallels" that are identified as intimate connections to Shakespeare's texts are not convincing. My conclusion is that, based on the evidence presented, Shakespeare cannot be considered as the annotator of this particular dictionary.

Why not just explicitly state "This is not Shakespeare's dictionary"? Because that is not how scholarship works. (Although I would add that were someone to purchase this dictionary because they think it is Shakespeare's dictionary, it would be a bad investment). It is possible to demonstrate with certainty what something is -- but it is much more difficult, and in some cases impossible, to know what something is not. The copy of the 1580 Alvearie in the University of Iowa's Special Collections library is virtually free of annotations, so it is impossible to know who may have owned or read it.

The lack of evidence, or evidence wrongly interpreted, does not prove anything. I do not say this because I am afraid of being proven wrong, or that my reputation will be in some way diminished (as they seem to imply when discussing the hypothetical objections of scholars). If Koppelman and Wechsler would like to see published critiques of my own work, they have several to choose from. Scholars are wrong all the time -- which is why we constantly challenge each other. This is a collaborative enterprise.

Who was the annotator? My assessment accords with some of the other initial responses: it was an active reader who demonstrated a contemplation of and engagement with language and language-learning. (Thanks to Andrew Keener for helping me to formulate this phrase--or, rather for allowing me to appropriate his phrasing. It's important to cite your sources). The so-called "trailing blank" (a blank endpaper with many annotations) is filled with corresponding English and French phrases, the signs of someone working through, and perhaps even enjoying, the differences in languages. The varied color of the ink also seems to indicate that a reader (perhaps even more than one) returned to this activity again and again.

What I offer here is a partial examination of some of the central pieces of evidence for the argument presented by Koppelman and Wechsler. This is what I consider to be a representative sample, and I have done this for two reasons. First, once the flaws in a particular methodology are identified, and crucial details have been assessed as inaccurate or misleading, it is not productive to continue. I have not attended to every last detail, and perhaps the authors would not be satisfied until every individual annotation and claim was analyzed and either confirmed or refuted. Second, I have attempted to take this seriously, and to assess the merits and shortcomings of the argument, as Koppelman and Wechsler seem to desire.

This is not part of my job -- this is a self-published book that has not gone through any kind of peer review process. But I do care about upholding certain standards of inquiry, especially regarding Shakespeare, the object of global cultural fascination. (This is also why I teach). If Koppelman and Wechsler would like to be granted a full and thorough scholarly review, then they can choose to pursue this through the normal channels. And, to state the obvious, this very essay is also self-published, though I welcome responses, critiques, and corrections.

The Argument

The Story Begins

The Scholarly Authority

The Expertise

The Evidence

The Booksellers vs. The Scholars

The Argument

An "argument" is a proof of evidence, a statement or proposition, and a summary or abstract. Here are five general areas I have found to be problematic.

An "argument" is a proof of evidence, a statement or proposition, and a summary or abstract. Here are five general areas I have found to be problematic.

1) Sources: Good scholars use reliable sources. Good scholars cite those sources. If you believe this is circular reasoning -- scholars rely on sources deemed reliable and reputable by other scholars -- then you need to understand that this is how modern scholarship works. Good scholars must also weigh different kinds of evidence, judging what can be considered reliable. This is necessary in order to avoid equating dissimilar sources -- such as, for example, an early reader's annotations in a book, and various myths, legends, and stories about Shakespeare.

There are seventeen pages of "Sources" cited in Shakespeare's Beehive. Some of them are current and reliable books and articles. Many of these sources are outdated, and a few highly suspect sources are accepted uncriticially. Beyond that, the sources are not used in acceptable ways. As I will outline below, at times sources are not cited at all for certain statements -- particularly when they incorporate critiques of the earlier edition.

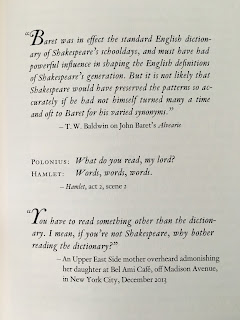

Quotations from sources are often reproduced without any acknowledgement of the original context of the quotation. One example which I examine in detail below -- two sentences written by T. W. Baldwin -- is considered important enough to serve as an epigraph. Yet it does not prove or provide the support that Koppelman and Wechsler seems to think it does. And then there is this example, from book jacket:

2) Resources: Koppelman and Wechsler insist that they are booksellers, and not scholars. I do not mean to impugn their worth or their expertise as booksellers. Those who work in the world of rare books have particular approaches and methods of their own. Unfortunately, this means that there are significant gaps and omissions in the resources on which they rely. For example, there is no real evidence that they use (or are even aware of) many of the standard online resources used in twenty-first century Shakespearean scholarship.

In their measured and thoughtful response, Heather Wolfe and Michael Witmore list some of the many resources that scholars, researchers, and librarians use on a daily basis. They also outline some of the issues and research questions that these tools can be used to answer, including a sophisticated (and computer-aided) analysis of textual proximity. They also attend to the importance of negative evidence -- that is, the absence of the kinds of evidence (especially annotations) upon which Shakespeare's Beehive depends. Koppelman and Wechsler often fail to mention details that might contradict their argument, refusing to consider any other kind of evidence. As Wolfe and Witmore state, in suitably forensic language:

"Scholars, however, will only support the identification of Shakespeare as annotator if they feel it would be unreasonable to doubt that identification. This is a fairly high evidentiary standard, since it requires one to treat skeptically the idea that this handwriting is Shakespeare's and to seek out counterexamples that might prove it false."There are many reasons to doubt.

3) Knowledge: You must know the field in which you are attempting to intervene. You must also acknowledge what you do not know about this particular field. Once you have done so, then you must educate yourself by reading the works acknowledged to be important, and by consulting with acknowledged experts. This is a matter of research -- in order to make a valuable contribution to an existing area of inquiry, then you need to know the foundational texts and methods for that area. You must also learn from your mistakes (I for one have made many) and keep reading, researching, and learning new information and new approaches. I will let a far more authoritative voice than my own pass judgment:

"it has a large number of misreadings, errors, misunderstandings and circular arguments. It displays some alarming gaps in its authors' knowledge as well as a degree of wishful thinking."That is H. R. Woudhuysen, and is quoted from the TLS review mentioned above. (It is also a comment that has rankled many booksellers unconnected with the Beehive project, demonstrating again a seemingly needless division). It is one thing to simply not know how scholarship works, or to simply possess gaps in your knowledge that you may not realize. It is quite another, however, to seek out expert opinions, and to then ignore them when their conclusions do not happen to match your desires. And this seems to be (alarmingly) the case in this instance, as the assessment of two of of the most well-known paleographical experts on early modern England was disregarded (as reported by Grace Ioppolo).

4) Methodology: Most of Shakespeare's Beehive consists of a search to identify potential connections between the annotations in the Alvearie and the texts of Shakespeare's works. Koppelman and Wechsler claim that the intimate connections they have "discovered" show that Shakespeare used this dictionary as a resource, finding particular words and phrases that he then inserted into his poems and plays. We know that Shakespeare was an acquisitive and appropriative reader -- because he was trained in grammar school, where he learned how to read like a Renaissance reader. And there are some connections between the commonplacing tradition and the kind of proverbial examples provided in the Alvearie, many of which might be considered as commonplaces.

The "parallels" that are identified here, however, are not convincing, sometimes consisting of only a single word or a constellation of words that are then matched to an area (or multiple areas) in Shakespeare's texts. As Michael Dirda wrote, in a review of the second edition in The Washington Post, "the book presents a relentless piling up of verbal parallels and echoes." The idea of a "parallel" will be considered further below -- there are serious methodological problems in relying on apparent parallels, and the method in the Beehive is not always applied rigorously, or even consistently. We would all do well to heed the advice Samuel Johnson gives in the preface to his edition of Shakespeare in 1765:

"I have been told, that when Caliban, after a pleasing dream, says, I cry'd to sleep again, the author imitates Anacreon, who had, like every other man, the same wish on the same occasion" (xxxvii).Caliban actually cries to dream again, but the thrust of Johnson's clever cautionary tale remains: if source study devolves into an unending quest to identify the precise origin of every word attributed to Shakespeare, then it has lost sight of what prompted a search for sources in the first place. Koppelman and Wechsler do not practice source study in the ways that it is currently defined, and I would argue that we should not consider it as a form of source study at all. If it is, then it represents the exhaustion of this mode of study: a dispiriting way to define a bookish Shakespeare. Could Shakespeare have used a copy of the Alvearie? Sure. Did Shakespeare write in the manner described? No.

It is good to remember that parallel lines point in the same direction, but they remain equidistant from one another and never intersect.

5) Rhetoric: I have written about the narrative appeal of Shakespeare's Beehive before (including the fictionalized Borgesian version of their own story that they imagine) so I will limit my comments here to the argumentative dimensions of their prose. I do understand that a critique of one's prose style can feel like a personal attack -- I will admit to an initial resentment when a critic once commented on my prose, but I had to admit that the criticism was correct, and that certain turns of phrase and writerly quirks inhibited a full understanding of my argument. As Michael Dirda -- a mainstream book critic for a national newspaper, and not a Shakespearean scholar -- wrote, at times the tangled prose resembles a certain Jedi master: "Not least, they grow tedious in their defensiveness about what they regard as an inestimable treasure."

The authors claim that their goal was to "present our findings in measured and non-polemical ways." While they are insistently (and frustratingly) careful and noncommittal, I do want to show some of the ways in which this strategy is polemical in its own way. I provide a kind of sentence diagram below that demonstrates some of the problems and inconsistencies in the book. To summarize, Koppelman and Wechsler repeatedly refuse to clearly articulate their argument. Instead, they have presented something of a mystery story that gradually unravels (at times in a misleading manner) as the protagonists make "discoveries" while constantly battling hypothetical critics who refuse to believe their conclusions. To appropriately acknowledge a potential counter-argument you must first make an argument, rather than attempting to lead readers on a journey that you hope will end in the same conclusion you have already reached. Preemptively ventriloquizing potential critics limits the terms of engagement, and, as a result, implicitly refuses the validity of any alternate forms of inquiry.

Tell stories. But make sure you do your homework first.

The Story Begins

One of my fundamental intellectual commitments and beliefs is that scholars should tell stories -- particularly scholars engaged in the seemingly arcane fields of bibliography and book history. I always try to begin with a story -- not an anecdote, but a crucial example or exemplar that indicates the methodology and the evidentiary basis on which my work depends. And so I entirely approve of the beginning that Koppelman and Wechsler give to their own story:

"On the evening of April 29, 2008, through joint venture, a bid of $4300 was placed on eBay for a book printed in London in 1580" (3).They go on to state that this particular item "carried from the beginning a sense of romance and intrigue" (3). And indeed, the first half of Shakespeare's Beehive is something of a detective story, as the investigator-protagonists reveal bits of evidence that they claim point toward Shakespeare, all the while confronting perceived doubters and attackers at every turn. As they later state:

"we began an informal study of the annotations, and gradually noticed a pattern of Shakespeare-related annotations, often in a surprisingly strong way. This is not to say that we found connections to the texts everywhere we looked; yet there were often enough for us to take note and begin to have fun with the idea, the grandest of all possibilities" (27).But this is not the whole story to the beginning of the story. In an interview with Adam Gopnik, recounted in "The Poet's Hand" in The New Yorker, Koppelman tells a slightly different story: the eBay seller had uploaded several images of the annotated dictionary, and the potential buyer noticed that two of the annotations were "drought in summer" and "yeoman of the wardrobe." Koppelman then states that

"my first thought was that these sound like poetic fragments. And then I looked them up and I found that 'drought in summer' was basically used as 'summer's drought' in 'Titus Andronicus,' one of Shakespeare's early plays. Later, we realized that 'summer' is a very, very common word in Shakespeare--he must have used it a hundred times--but 'drought' only one time."This means that before they had submitted a bid for the book, Koppelman and Wechsler thought that Shakespeare might be the annotator of the dictionary -- or, at the very least, that there was an intriguing connection to one of Shakespeare's texts. As Gopnik puts it, "They had, they confess freely, intimations of immortality in the pages." The first thing I tell my students is to Stop Thinking & Start Working -- that is, work through the material first, and let an argument emerge from that work. Starting with a predetermined argument means that you are in danger of simply finding what you already wanted to find.

One interpretation of these statements, then, is that the investigation conducted by Koppelman and Wechsler was motivated by the (implicit or explicit) notion that they were in possession of Shakespeare's dictionary. They then set out to find evidence that would show that what they wanted to be true actually was true. A more generous interpretation is that an initial hint led to an enthusiasm that was channeled into a search for possible or plausible connections between Shakespeare and this book.

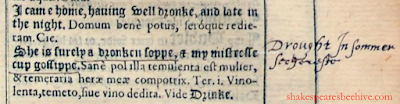

But what about this particular annotation? "Drought" is indeed a rare word in Shakespeare (although a quick search shows that a variant, "drouth," appears at least twice, once in the early narrative poem Venus and Adonis, and another in the collaborative late play Pericles). The phrase "summers drought" does appear in Titus Andronicus:

Granted, this is not the same as "Drought In Sommer," but it might be considered a parallel. Why did the annotator insert the comment here? It appears at the very end of the list of examples that appear under the heading "dronken." It likely does not have anything to do with the adjacent underlined phrases: "a dronken soppe" and "my mistresse cup gossippe."

The more likely possibility is that the annotator inserted an entry that was not included in the 1580 edition of the Alvearie at the appropriate alphabetical place (this happens countless times). This is the end of the "Dr-" section, before "Du-" begins just below, so this is where an entry for "Drought" would be placed. That is, the annotator may be improving and adding to the usefulness of the dictionary, over time. Just below the phrase "Drought In Sommer" is the word "Sechereste," which is the French equivalent for "Drought" -- so here we can see a reader engaged with language (and perhaps language-learning).

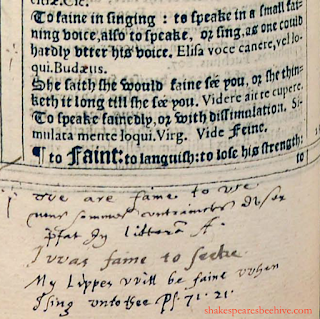

In a further twist, Koppelman and Wechsler examine this particular annotation in a section devoted to the discovery of biblical citations (36-38) -- although they do not mention the French translation of the word "Drought." It is not marked as a biblical citation, as the annotator does elsewhere -- such as in the group of annotations below the the word "faine."

The final two lines read as follows:

"My Lippes will be faine when

I sing vnto thee Ps. 71. 21."

This is indeed a quotation from the 21st line of Psalm 71. At any rate, as Koppelman and Wechsler state, although the "Drought In Sommer" annotation was one of the very first they considered -- before they even bid on the book -- it was one of the last they identified as a biblical citation, in part because it was not marked as such. It is a phrase from Psalm 32, which appears variously in early modern bibles as "drought of summer" or "drouth in sommer" (though they do not identify "drouth" in Venus and Adonis or Pericles).

The point of this discussion is the train of thought:

- 1) The phrase that first caught Koppelman's eye on eBay was quickly identified -- correctly or incorrectly -- as a parallel to Titus Andronicus, thus lending the impression (or the hope) that the dictionary belonged to Shakespeare.

- 2) This initial impression led to the bid for the item, which was successful.

- 3) Upon receiving the book, they set about examining it, and found what appeared to them as numerous connections to Shakespeare's texts. Thus, they began attempting to prove that the dictionary was, indeed, annotated by Shakespeare.

- 4) As part of this attempt, they tracked biblical citations. The appearance of a parallel in an early play like Titus could also demonstrate the relatively early use of the dictionary, in the 1580s or early 1590s.

- 5) The realization that this particular annotation could be considered just such a biblical citation happened relatively late in the process, after several other similar citations were also identified. It was thus used to confirm that a) it was Shakespeare's dictionary, just as they had always hoped, because it contained a personal memory of a biblical quotation, and b) that the Alvearie influenced Shakespeare's early development as a playwright, as they had always suspected.

The Scholarly Authority

In the prologue to Shakespeare's Beehive, Koppelman and Wechsler admit to the "sense of romance and intrigue" they felt about the volume, protesting that this feeling was indeed both genuine and intuitive since

"we had not yet come across Mr. T. W. Baldwin and his pronouncement, a conclusion that we imagine will represent a certain portion of the debate going forward" (3).The "pronouncement" they refer to, which I will return to below, is taken from Baldwin's magnum opus, and it is quoted as an epigraph to to the book:

The title of Baldwin's monumental two-volume work of scholarship -- William Shakspere's Small Latine & Lesse Greeke (University of Illinois Press, 1944) -- alludes to lines in Ben Jonson's (in)famous dedicatory poem in the First Folio, where he declares that "And though thou hadst small Latine, and lesse Greeke, / From thence to honour thee I would not seeke / For names." Jonson then lists some of the great classical Greek and Roman writers of both tragedies and comedies, thus placing Shakespeare amongst the ancients.

(Incidentally, "Shakspere" as used by Baldwin is not an error -- the spelling of Shakespeare's name has fluctuated over time, and deserves a discussion of its own. Baldwin's use was common at one point, since it relies on the spelling Shakespeare used in his surviving signatures. In this case, the evidence from manuscript -- "Shakspere" -- was considered to be more authentic than the evidence from printed sources -- "Shakespeare").

The first part of Baldwin's book is dedicated to historicizing the myth of Shakespeare's unlearned and untutored genius, as a writer without proper training in classical languages. (It has, however, been argued that the "hadst" is a conditional -- i.e., the lines should be interpreted as "even if you had small Latin, and even less Greek, you are worthy to be considered among the ancients" -- although the dominant understanding interpreted the lines as indicating a distinct lack of learning on Shakespeare's part). The remainder of Baldwin's massive study is dedicated to rebutting this unlearned characterization of Shakespeare by showing "as much as possible of the formal education to which he was subjected, not only directly, but also indirectly through absorption" (1:vii).

Baldwin's massive study has been extremely influential, although in part due to its bulk, it is now more admired and consulted (especially in its online incarnation) than actually read. It has long been a favorite resource of mine, not least because Baldwin taught at the University of Illinois, my undergraduate alma mater. (His collection of early modern books was purchased by and is now accessible in the UI Rare Book & Manuscript Library and you can see a printed catalogue of the collection here). Baldwin's stated goal was to "write on 'The Evolution of William Shakespeare,' in the sense of how under the existing circumstances he worked himself out." He stressed that

"Whether or not Shakspere ever spent a single day in petty or grammar school, nonetheless petty and grammar school were a powerful shaping influence upon him, as they were, and were planned to be, upon the whole society of his day" (1:vii).

Baldwin again emphasized and qualified his goal:

"I have in no sense whatever written or attempted to write a book or books on Shakspere's education. I have attempted merely to present in as orderly fashion as my own nature and that of the materials would permit all the facts so far as I now know them which appear to me to have a bearing upon the question of Shakspere's formal education, and to present my own conclusions upon those facts" (1:ix).

He also commented on his own methodology, particularly on the sensitive and questionable matter of "parallels" between Shakespeare's works and the sources upon which they were based -- a difficulty that Koppelman and Wechsler should confront, as well. Baldwin states that

"I have not consciously based any conclusion on mere parallels as such. Instead, I have first attempted to put Shakspere's statement into its total pertinent contemporary background, in order to determine the focus of infection. Once we know that, it is then possible to get some judgment as to whether the focus is proximate to Shakspere or merely ultimate" (1:xi).The scientific and forensic nature of these remarks -- identifying patient zero for an "infection" and thus identifying a specific source for a passage in Shakespeare's works -- demonstrates Baldwin's scrupulous practice as a scholar: historicize and contextualize. At the same time, the admission of uncertainty demonstrates the difficulty in identifying a particular source for ideas or phrases that were simply a part of general cultural knowledge. His goal was not to show what Shakespeare read or knew -- it was to show what he may have read and may have known, based on the evidence of contemporary educational practices.

A "pronouncement" by the magisterial Baldwin, in his (quite literally, weighty and substantial) book, is the condition of possibility for the argument Koppelman and Wechsler present:

"Our speculation, the driving force behind our book, is that Baret's Alvearie is indeed part of the canon of source material, and is predicated on Baldwin being correct: that in the course of his intellectual development, Shakespeare did turn to Baret, and turn to him 'many a time and oft,' not just casually once or twice, or a modest number of indifferent times" (9).This remark tells us that the success of Shakespeare's Beehive depends on the validity of Baldwin's statement. Koppelman and Wechsler reiterate their dependence on Baldwin multiple times, including this somewhat defensive statement that just precedes the last quotation:

"In consideration of T. W. Baldwin's assessment, of which we did not have the slightest inkling when we made our bid, we cannot help but wonder after studying the book for as long as we have, had more people investigated the accuracy of his claim, then, no doubt, the whole notion of a copy of Baret would be different, akin to a copy of Shakespeare's Holinshed, his Plutarch, his Ovid, or his Florio. But essentially there never was a critical uproar generated, and so the Alvearie never made its way into the pantheon of exalted sourcebooks on which the plays were partly built" (9).This remark tells us that, first, they did not know about Baldwin's assessment until after they purchased the volume; their intuition before buying it (see above) was thus later confirmed by a respected scholarly authority. Second, that no one followed up on Baldwin's suggestion -- considering the massive and endlessly allusive nature of the two volumes, this is not surprising -- but, if only someone had, the idea of Shakespeare annotating an Alvearie would not be surprising.

There are two avenues of investigation here: 1) to contextualize Baldwin's statement, and 2) to survey the responses to Baldwin's assessment of Baret's dictionary and its relation to Shakespeare.

1) What did T. W. Baldwin say about Baret's Alvearie?

The only part of Baldwin's analysis that is quoted by Koppelman and Wechsler is the statement reproduced in their epigraph, consisting of two sentences. They do not explain in what context these two sentences appear. As my own analysis shows, however, this is a case of selective and convenient (if not irresponsible) quotation. For example, they do not cite this statement from Baldwin, which appears about 200 pages before the one that they do quote:

"One would also expect John Baret's Alvearie to have been used for reference in grammar school. It was printed in English, Latin, and French, with some Greek, by Henry Denham in 1573 [sic], and again with the Greek strengthened in 1580. It was thus of some currency, but not widely used" (1:529).This is a striking qualification of Baldwin's subsequent assessment -- but again, perhaps unsurprising in such a lengthy compilation. But Koppelman and Wechsler do not even consider the immediate context of the remark they use as their primary epigraph: Baldwin's attempt to determine how Shakespeare may have used Baret's Alvearie, and by extension the wider tradition of English dictionaries.

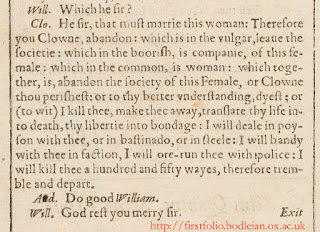

Baldwin's only extended example focuses on Touchstone's speech which concludes the first scene in Act 5 of As You Like It.

The speech is a clever rhetorical maneuver -- "a construe leading to a translation from courtly English into the vulgar," according to Baldwin (1:715) -- which would be familiar from grammar school training, as well as the dictionary tradition. And if Shakespeare "used any such dictionary at all, it would necessarily be either Baret or Huloet (1:715; the latter is a reference to an older dictionary that had been published in a revised form in 1572). Baldwin finds several possible parallels between Touchstone's speech, and entries in dictionaries, including Baret's. For example, "abandon" is defined as to "leaue" in Baret (it is also the very first entry); "company" is one definition of "society" in Baret, as is "perish" for "die," although there are other possible sources for these comparisons. Baldwin admits that the likeliest direct source of "woman" for "female" comes from Huloet. Again, the important issue is not finding a direct source, but rather that "in every instance Shakspere is following the dictionary tradition in his definitions" (1:717, my emphasis) and that, among the likely sources within English dictionaries (which Baldwin admits Shakespeare did not necessarily use) Baret seems the closest (though this is arguable).

It is in this context that Baldwin makes his "pronouncement" about Baret's Alvearie -- a statement that is far more qualified (if not specious) than the statement quoted in isolation. Baldwin is not entirely convinced that such parallels can prove anything taken on their own, and he not only admits other possibilities for English dictionaries, but identifies a common source: the French-Latin dictionary upon which many of them were based. Could Shakespeare have used the Alvearie to find his synonyms? Perhaps, although there are other sources he could have consulted, as well. The point is that Touchstone is imitating a grammar school exercise. And one would think that Shakespeare need not consult a dictionary to find out that a "female" is a "woman."

Koppelman and Wechsler do not mention the example of Touchstone -- the foundation on which Baldwin's pivotal pronouncement is based. This is because not one of the entries Baldwin cites are annotated in their copy of the Alvearie, and they mostly limit their own analysis to the annotations. In the only instance their scholarly authority could find of a potentially direct connection between Baret and Shakespeare, the book fails to live up to its billing.

2) What did other scholars say about T. W. Baldwin?

Koppelman and Wechsler lament the fact that no one followed up on Baldwin's suggestion, although the carefully qualified nature of his claim may be one reason for this. However, the assertion is also not exactly true: only two years after Baldwin's study appeared, his conclusions regarding Baret were challenged by James Sledd (who was at the time writing his dissertation on the Alvearie) who called it an "Elizabethan Reference Book."

Sledd's main focus is on Baret's proposals for reform in English orthography (i.e. spelling) which are outlined in the "preambles" that serve as a preface to each alphabetical section. In this, as in everything else, Baret "represents the common knowledge and opinion of his time" (162). But he also identifies the intended audience for the Alvearie: beginning students, and not advanced scholars. Sledd quotes from (and translates) the Latin dedication, which states that it is "not so much for the learned" [qui doctore non egeant] "as for those who are yet untaught" [quorum gratia hoc quicquid est operis primo susceptum est] (151). It was a reference book intended to be used by schoolboys and undergraduate students.

That does not mean, of course, that this is the manner in which the book was always used -- although it was recommended to students in instructional manuals as a suitable source for studying translation, for example by John Brinsley (in 1612) and again by Charles Hoole later in the seventeenth century. As any scholar will note, praxis often fails to live up to theory, and while it certainly seems to have been used in classrooms across England, it was also likely available to many other kinds of readers as well.

Sledd also challenges Baldwin's "expected authority" on Baret's Alvearie: while it remained a useful book for nearly a century (if not beyond) it certainly was not widely popular, since it failed to survive the competition offered by other dictionaries (it was never reprinted after 1580). And further, in a lengthy footnote he states that

"Perhaps, if Shakespeare actually used the Alvearie, as Professor Baldwin thinks probable, the scales might be tipped in favor of the belief that it was, for some time, 'the standard English dictionary'" (154n16).The expert on the Alvearie contests Baldwin's claim -- the claim that underlies the entire Beehive enterprise. The argument is as follows:

- 1) According to Sledd, the Alvearie was not as popular as Baldwin thought (since it was never reprinted again, as opposed to other, more popular dictionaries, which were). Admittedly, instructions in the seventeenth century urged students to consult existing copies; however, Sledd seems to find the idea that Shakespeare consulted one -- at least on the basis of it's supposed popularity -- to be quite unlikely.

- 2) The only way to prove Baldwin's claim that it was the "standard English dictionary" would be to prove that Shakespeare did indeed use it, thereby confirming this (unlikely) claim. Only in that (unlikely) circumstance, that is, could Baret's Alvearie be considered "standard."

- 3) Baldwin's (uncontested) claim is cited by Koppelman and Wechsler, which they use to help prove that their copy of the Alvearie was annotated by Shakespeare.

Koppelman and Wechsler do not cite Sledd's article, but they do cite a subsequent article written by him, "A Note on the Use of Renaissance Dictionaries." Again he urges scholarly caution, particularly when attempting to identify or interpret textual parallels. (In this he is similar to Baldwin's skeptical stance toward parallels). Sledd here states that parallels found between dictionaries and literary works (e.g. Chaucer, Shakespeare, and Milton) are only useful as a matter of interpretation. That is, a parallel can help us understand, in a more accurate manner, what a particular phrase meant to its original readers:

"Of parallels like these, when they are cited merely to clarify, the only complaint could be that one might better occupy himself than in collecting them. The right parallel may do still more, and establish a source. But the banality needs repeating that the wrong parallel, or the parallel wrongly interpreted, may confuse and mislead" (12).The example he gives from Shakespeare comes from the play we know now as 2 Henry VI. In the first scene of the play, in both the quarto (1594) and folio (1623) texts, Duke Humphrey addresses the "Braue Peeres of England, Pillars of the State." Sledd argues that, based on Baret, this phrase may contain an etymological pun, since "Peeres" is defined as "Pierres" which are like the "corner stones and pillers in a building." His point is not that Shakespeare found the image in Baret, but that what seems like an innocuous and straightforward phrase could be interpreted as a pun based on the information in the Alvearie. There is no annotation on this entry -- although we can see the annotator once again inserting an entry in its appropriate place: in this case, "Peepe of daye" between "Peele" and "Peeres," with the added instruction "vide Breake."

This is a cross-reference within the Alvearie. After the long set of examples under the entry for "Breake" there is a short additional entrie for "the Breake of the daie." The final example given for this entry is "I will get me away to morowe at daie breake, or at peepe of daie." So here we have an engaged and active annotator who 1) inserts the word "peepe" where it would/should occur in the dictionary, and 2) inserts a cross-reference to another entry.

My main point here is both argumentative and evidentiary: first, one of the pillars of Shakespeare's Beehive is the statement of T. W. Baldwin, a statement which, upon further review, does not offer the unqualified support that Koppelman and Wechsler think it does. Second, this is not how source study is currently conducted. Even scholars who spent their careers finding textual "parallels" between literary texts and dictionaries admit that they can easily confuse or deceive, and as such they need to be carefully considered and interpreted within the appropriate context. These parallels may be able to help illuminate what Shakespeare was trying to say, but that does not mean that he needed to consult a dictionary to say it.

The Expertise

Both Koppelman and Wechsler are experienced booksellers, and they spend some time discussing and explaining their experience with -- and devotion to -- "old books." Again, it is not my intention to question the particular expertise of these two rare booksellers as booksellers. It is my intention, here and throughout this essay, to note some of the differences in the way "expertise" is defined. I will proceed here by examining the issue of expertise in three ways: Money, Paleography, and Forgery.

1) Money

They state that, once they received their purchase,

"As rare booksellers, we then began to do what we have done repeatedly. We started to describe an item new to our inventory with the goal of reaching the utmost limits in terms of appeal" (3).This is, they stress, "not meant to sound magnanimous" (3-4) since the goal is, obviously, to make a return on their investment. "Add too much luster and gloss to your descriptions, and it will seem as though you are trying too hard" (4). Their overarching goal is "to provide, in due course, the actual dictionary with a more appropriate home" than its current location in a private security facility ("A Note to the Reader").

As the conclusion to "A Note on the Authors" attests, this goal required the formation of an LLC to handle "the possibility of particularly sensitive reactions that have for some time been anticipated" (417). What are these "sensitive reactions"? Commercial transactions are nowhere mentioned explicitly. Yet as Gopnik reported -- more directly -- in his New Yorker story, the acknowledged doubts surrounding the identity of the annotator has not discouraged their "eventual ambition to sell the Alvearie to a good home ... for a good sum." (The Folger Shakespeare Library is mentioned as their "dream," since presumably it would offer not only a good price, but a validation of their entire enterprise -- another kind of institutional authority to pursue). And Forbes magazine even used this "discovery" to give entrepreneurial advice: not only can money be made in an endeavor like this, but it represents the kind of industrial transformation that entrepreneurs need to succeed!

At any rate, Koppelman and Wechsler identify themselves as dealers who have "independently spent more than two decades working with rare books" (indicating their experience) and list the various antiquarian booksellers' associations they belong to (indicating their recognized authority and prestige). But they only gradually reveal the results of their collective expertise, choosing instead to first recount a variety of myths and legends surrounding Shakespeare's earliest years in London. I have written about this before, in my first essay on the Beehive, which can be found here, and in my book, which can be found here -- so I will only add this: in the conclusion to their chapter on this matter, they state their belief that

"Shakespeare was a part of a 'proofing' group, and acquired his copies of Baret and Holinshed through the book world, an introduction to which he was likely given by [Richard] Field. Thus were registered some of the initial, and fully necessary, deposits into Shakespeare's library" (26).It is perhaps not a coincidence that two booksellers would remake their object of study in their own image, just like the booksellers in the past (like Capt. William Jaggard) who also turned Shakespeare into a bookman.

2) Paleography

Koppelman and Wechsler have thoroughly examined this material artifact, although for reasons of safety and preservation, they state that they now rely on the digital facsimiles that they have made available (for free, registration required) online. Their terminology often differs from what I would use -- e.g., what I would call a kind of "trefoil" (seen in the example from Psalm 71 above) they call a "mouse-foot," which is charming enough that I might adopt it myself. But they have spent years with this extant physical object from the past, transcribing its (often difficult to read) annotations.

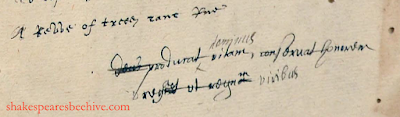

The descriptions that booksellers produce can provide very valuable information, and transcribing annotations certainly counts as valuable. However, their paleographical skills have been challenged, particularly in one important case, a phrase written in secretary hand on the so-called "trailing blank." They claim that it reads "bucke-bacquet" which they interpret as a unique phrase from Merry Wives of Windsor -- "buck-basket." Aaron Pratt has argued (successfully, to my mind) that the phrase should read as "bucket bacquet," that is, and English word and its French equivalent, exactly the kind of translation exercise that fills the page.

In the second edition, they return to this issue, and seem to respond directly to Pratt's critique, or, possibly, similar objections to their interpretation that they came across elsewhere. I don't know because they do not cite any source for the differences in this paragraph between the first and second editions. As you can see here, they claim that only a "rushed contention" would maintain that the phrase reads "bucket bacquet" (Pratt's online essay was posted not long after the launch of the first edition).

They then claim that an "extreme close-up examination" (264) supports their point. And of course, no one else has access to the artifact to conduct a similar "close-up examination."

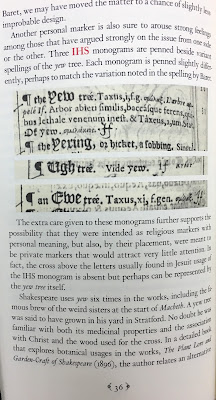

Part of their reasoning here depends on another paleographical problem that is also an error. They dedicate a section to the annotations surrounding entries for the yew tree. The French equivalent for "yew" is "if." In the second edition Koppelman and Wechsler state that one of the "if" annotations is actually an "IHS" monogram, which they claim supports a complicated string of religious associations that center on Shakespeare's supposed Catholicism.

However, in the first edition, they claimed that all three annotations were "IHS" mongrams:

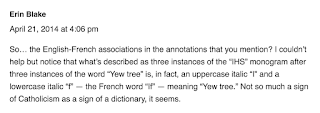

They cite no source for this alteration, and although it is conceivable that they came to this conclusion on their own -- the second example is clearly the word "if," imitating the typography of the dictionary -- it is more likely that they read the comment that Erin Blake, a curator at the Folger Shakespeare Library, made on the Wolfe and Witmore post (this comments was also cited in Woudhuysen's TLS review).

There are thus significant problems with 1) their paleographical interpretations, and 2) their failure to acknowledge the scholarly sources that they seem to have relied on.

Another problem is that they do not note when annotations are written in different colors of ink, which signifies, at the very least, the passage of time: an annotator may return again and again to the same place in the text -- or a different annotator may add or respond to an existing annotation. In Shakespeare's Beehive all the annotations are printed in red type, thus flattening and unifying what are often disparate markings on the page.

They are keen to explain their understanding of early modern paleographical practices, as a way to explain away some of the significant variations in the handwriting of the annotations. Some are in secretary hand, but many others are in italic, and some of the latter are conscious attempts to imitate the typography of the book. The issues at stake are as follows: 1) Did the same person make all the annotations? 2) When did this person make the annotations?

The six surviving signatures of Shakespeare are all in secretary hand, and they all possess some discernible variations. Handwriting at the time was not as standard (and probably still is not as standard) as we might think, which is 1) why it is very difficult to discern and identify a particular hand, since an individual's handwriting was variable, and 2) why it can be difficult to discern how many different individuals made marks in any particular book. It is also not impossible that Shakespeare learned to write in an italic hand. The pages in the Alvearie are often cramped (though the margins are wide enough) and so a reader could perhaps have varied the hand to suit the available space. So it is plausible that one reader made all the annotations -- but considering that the Alvearie was still recommended for use a century after its publication, it is extraordinarily difficult to pin down a date, or an identity (or identities) for the annotators.

At the bottom of the so-called "trailing blank," for example, there is a Latin motto written in a hand that appears to me to differ in some respects from the other annotations on the page. This motto has been amended by reader (that is, probably a different reader) who seems to write in a different hand with what is certainly different ink. Two words are inserted, one word is scratched out, and two other words have been altered, evidence of someone responding to and altering the original motto.

This often happens in early modern books which passed from owner to owner -- I have seen many, and one in particular has made an indelible impression on me. I have not yet fully explored this particular set of markings, but to my mind it is one of the more interesting features in this book.

My real interest in the paleographical question, though, is the use to which it is put in the Beehive narrative. Once they have established that early modern handwriting could be very variable, Koppelman and Wechsler insist on equating the variation in hands with the singularity of the annotator.

"the tremendous variation that we see present in the formation of letters throughout the book matches, in great detail, the wide variation found in the letter formations on the trailing blank. The Elizabethan attraction to variation is here in full bloom, and the variation is evident even in a single annotation" (65).If everything is variable and nothing is stable or consistent, then the only explanation must be that a single annotator used a number of different hands, even within a "single" annotation. In their complete transcription of the annotations (available by request) they do acknowledge the variation in inks:

"One can see even at first glance, in looking at the ink, that clusters of annotations do not always belong to a single moment of composition; that is, they are built upon over multiple entries" (3).However, they still consider all the markings at a specific place in the book as a "single" annotation, and they are transcribed -- both in the PDF and in Shakespeare's Beehive -- in a manner that does not signal any of these variations. This is a serious mistake, but to their credit they have made the images available online, if you submit details about your identity. So, the differences in ink may indicate either that 1) there were multiple annotators (and there are in fact multiple annotators of this book, it is just that other annotations are not considered or mention), or 2) if it was a single annotator, this person annotated certain entries at different times.

I do not agree with the conclusion that the significant and visible variations in both the handwriting and the ink must point to a single, identifiable annotator. To be sure, I would have to inspect the book in person, and although I've been formally trained in paleography by a well-known expert, this is not my main area of expertise. But I also disagree on argumentative grounds -- in an attempt to gloss over a significant problem, they have produced a narrative that is perhaps possible, but is neither straightforward (nor logical). They do not explain exactly how the variations in the annotations in the text match the variations in the "trailing blank." The conclusion here is that, as in so many other cases, paleography alone is inconclusive.

They conclude with an accusation aimed at paleographical experts:

"What we are contending on the subject of the handwriting comes down to this: if the principal contention that paleographers have to stand on in refuting the extraordinary linguistic evidence in our copy of Baret is based upon the Italic irreconcilability with someone of Shakespeare's background, this reasoning is going to prove disingenuous. Irreconcilability of someone of Shakespeare's background and the works is, after all, the battle cry of what are termed the anti-Stratfordians or anti-Shakespeareans" (76).That is one big "if." They have attempted to limit the question of paleography to only one issue: the presence of both secretary and italic hands, and the fact that there are no extant Shakespearean manuscripts in italic. They have also preemptively spoken for paleographers, rather than asking esteemed paleographers for their expert advice. (And, as noted above, when they did ask expert paleographers, they ignored the conclusions). Secretary vs. Italic is certainly not the only issue at stake -- any determination based on paleographical evidence would necessarily be the result of a painstaking, methodical, and scrupulous investigation of the artifact by an acknowledged expert in the field. Anyway, as they go on to state, "Shakespeare was nothing if not an exception to the rule" (which rule?) and so inconsistencies are to be expected.

The final sentence quoted above implies that any paleographer who dares to differ with their interpretation of the evidence (or at the very least, their interpretation of this one particular issue) is equivalent to an anti-Shakespearean. This is, if not an illogical insult, at least a counterproductive and exaggerated rhetorical flourish. Anyone who wants to be taken seriously should know better than to make a statement like this.

The conclusion to the chapter on paleography takes a rather disheartening turn. I understand why Koppelman and Wechsler felt the need to include this section, but at least from the perspective of a scholar, I find the mode of argumentation to be somewhat disingenuous. At the end of a discussion of the variations in Shakespeare's six attested signatures -- authenticated because they appear on legal documents -- they write that if we found such variation in signatures on a sourcebook, it would be easy "to see how the signature would rather swiftly be denigrated as a forgery," since it "does not bear the irrefutable imprint of a legal document" (73). Experts on the law might say that such documents are not necessarily "irrefutable," and at any rate, as Margreta de Grazia has demonstrated, our standards of accuracy and authenticity have been shaped over time, in ways that we have often overlooked. There is no signature in their copy of the Alvearie -- and beyond this, every signature of "Shakespeare" that has been found on an early modern book has been classified as a forgery. So I will admit the statement serves a certain purpose here.

Koppelman and Wechsler then make the following statement:

"Our copy of Baret's Alvearie and the marginalia it contains is nothing if not genuine. Our own eyes and experience told us this from the outset, and it was only more substantially reinforced the further we worked our way into the analysis. [...] There is no conspiracy to be found among the annotations in our copy of Baret. Only the most bitter, misguided, and misinformed responses -- and with all due respect, there are bound to be many -- would suggest otherwise" (74).They continue by stating that the annotations are "wholly the product of someone's organic and very diligent approach toward the book and stand no chance of being understood as the product of a calculated attempt to deceive" (74).

What they seem to be saying is this:

- 1) The annotations are not forgeries, but the product of a sixteenth (or seventeenth?) century reader (or readers?). Their own study of the book has convinced them (and rightly so) that the annotations are indeed genuine. The mention of a "conspiracy" may also be intended to exculpate the two booksellers -- i.e., the annotations have never been forged by anyone, including its current owners.

- 2) Only the most bitter and misguided person would suggest forgery. At several points in the book, they express apprehensions (and rightly so) about the ways in which anti-Shakespeareans will respond to their study, and this statement may be directed at them. They also express the hope that, by proving Shakespeare helped to educate himself by consulting this dictionary, the objections raised by these anti-Shakespeareans will be put to rest.

- 3) Because the annotations are not forgeries, and because only the misguided would suggest otherwise, the only valid response is to take their claims seriously.

- 4) This is my own critical assessment, and not necessarily what Koppelman and Wechsler intended, but I do have to say that this invocation of the most basic bibliographical fact -- this book has survived for over 430 years, and it is real, and it is annotated by an early reader -- is a rhetorical maneuver that exploits what we certainly know (it exists) in order to confirm what we don't know (the interpretation that Shakespeare was the annotator).

Near the chapter's conclusion, they discuss the example of a copy of Florio's translation of Montaigne, published in 1603, that has Shakespeare's signature on the title-page. It was bought for the British Museum by Frederick Madden (and in unrelated research, I've recently discovered that Madden's blessing of the signature as genuinely Shakespearean changed the spelling of Shakespeare's name in the first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary). The signature is now considered to be a forgery (or, "It is currently not in fashion to promote the validation of the Montaigne signature" [75] -- note also how Koppelman and Wechsler include "Florio" in their list of verified sourcebooks above). Even so, they cite Frances Yates's conclusion that, whether genuine or not, the signature "probably represents a truth" -- meaning, I believe, that based on Shakespeare's works, we can determine that he did indeed make good use of Florio's translation -- just not this particular copy of that translation.

They thus conclude that "something similar may soon also be said about the annotations in the copy of Baret in question: The annotations are most definitely genuine, and, whether Shakespeare's or not, they represent a certain truth."

This is a puzzling statement that appears to draw several conclusions:

- 1) The evidence they present in the Beehive will soon be considered so overwhelming that the Alvearie will take its place alongside the canonical sourcebooks, like Plutarch and Holinshed.

- 2) The annotations are genuine -- meaning that they are not forgeries perpetrated by Koppelman and Wechsler, or anyone else. This statement gets close to admitting the value of the annotations beyond Shakespeare, as evidence of an early modern reader engaged with language.

- 3) Even if the annotations were not written by Shakespeare, they still represent "a certain truth" because of the intimate connections they have found between the dictionary and Shakespeare's works. That is, they hope to demonstrate (or believe they already have) an irrefutable connection between the Alvearie and the texts of Shakespeare. (This claim is not irrefutable).

- 4) Thus, the most likely scenario is that Shakespeare himself was the annotator. This is, for Koppelman and Wechsler, far more likely than a) a later reader who was familiar with Shakespeare's texts, and made these connections -- although since none of the annotations mention any connection to Shakespeare, it was left to the two booksellers to discover this; or b) that someone "just got really lucky" (364) and happened to annotate entries that Koppelman and Wechsler would later claim to have connections to Shakespeare.

The Evidence

Faced with the inevitable intractability of paleographical evidence, and the inherent unreliability of the myths of Shakespeare's "lost years," Koppelman and Wechsler turn their attention to so-called "personal markers" -- annotations which they claim reveal some of the personal interests and commitments of the annotator. I will say this: I am extremely skeptical of this particular method -- of attempting to discern a "personality" from manuscript annotations. This is a problem inherent in any study of early modern readership: the various kinds of marginalia and signs of use are often difficult, if not impossible, to interpret with any certainty, even when there seems to be a relatively consistent system at work. This is why it has been so difficult to produce generalizations about early modern readership -- the praxis simply cannot be reduced to theory. (As always, interested readers should turn first to William Sherman's Used Books). I have spent a lot of time examining the books of one of the most famous and idiosyncratic Renaissance readers, and even in this extraordinary case, I would hesitate to make any conclusions about his "personality," beyond the most basic emotional and intellectual feeling, common to many scholars, of a familiarity with an object of study from the distant past.

Koppelman and Wechsler start by comparing their copy of Baret with a remarkable annotated copy of John Higgins's revision of Huloets Dictionarie (1572). The copy seems to have been owned by Higgins himself, and the extensive annotations may indicate that he was preparing a revised edition that was never produced. (They do not cite their source -- and reputable scholars always cite their sources -- but you can read more about this book in Heather Wolfe's brief analysis at the Folger's "Collation" site). Contrasting this book with their Alvearie, Koppelman and Wechsler write that

"The personality of the annotator is lacking in nuance, and it is unlikely that one could find in the swirling mass of annotations any personal effects; it is simply a brute force task that, however awesome, obliterates information with the excess of information it provides" (15).This statement results from an application of entirely subjective criteria which takes, as its implicit premise, that annotations should represent the "personality" of an annotator in a "nuanced" fashion. They do not ground their knowledge in the standardized ways in which Renaissance readers were taught to read nor do they consider the particular task this work was intended to fulfill (even though they do admit that the copy of Huloet is "aberrational"). Instead they denigrate the "brute force task" which lacks any of the allegedly unique and compelling qualities of their Alvearie. This also implies that there is indeed a nuanced personality that is evident in the Alvearie annotations (it is not explicitly evident, hence requiring them to carry out minute investigations to explain how it might be considered "personal"). Besides, it would be difficult to "find people who actually care" (16, emphasis in original) about a dictionary annotated by someone we don't know or already care about.

And so they find Shakespeare because Shakespeare is who they -- and we -- want to find.

(Or buy).

In this section, I will consider the following kinds of evidence presented in the first part of Shakespeare's Beehive: the typographic imitation of the letters "W" and "S," and the significance of biblical quotations among the annotations. I will use these two kinds of evidence -- particularly the latter -- as case studies that I believe are representative of Koppelman and Wechsler's methodology. I also think my general assessment of this methodology is quite similar to my assessment of other kinds of evidence they present (although the individual details are obviously different) such as biographical speculation, or interpretations of the works which purport to find Shakespeare's thoughts or intentions in the works. I will conclude this section with a brief mention of some of this other evidence.

"W" & "S"

The first piece of evidence presented as a "personal marker" is the statement that the annotator only imitates the typography of two lead capital letters: five times with "W" and three times with "S," with all the instances occurring in the alphabetical sections of "W" and "S." They do state, however, that

"as evidence in support of our hypothesis, caution would, no doubt, be expressed and be expressed strongly" (32).Indeed -- although they do also go on to imply a sub-conscious preference for these two convenient initials on the part of the annotator -- and who else could have had these initials? The problem is that this "preference" is simply not true. And even Koppelman and Wechsler admit so, albeit in a footnote to a much later passage in the book:

"We should note that in a few instances, a majuscule letter 'B' bears some resemblance to the capital 'B' as printed in Baret. But these 'B' examples are spread out and not contained within the letter, as is the case with the 'W' and 'S' imitations. Also, the majuscule 'B' letters as printed in Baret are closer -- unlike the attempted copies of the 'W' and 'S' -- to genuine representations of the majuscule 'B' as seen in period handwriting" (394n77).I have not done a complete survey of the annotations which imitate printed typography -- many of which just happen to be lower-case, rather than upper-case, in my limited research -- and only a complete survey could answer the questions that this claim raises. This entire discussion also needs to be considered within wider practices of handwritten typographical imitation in manuscripts, as well. But I will say there are other capital letters that seem to imitate the typography in the Alvearie, some of which are capital letters.

Here are the implicit judgments being made about the initials "W" and "S" :

- 1) "W" and "S" are not the only typographic majuscules imitated in a manuscript annotation, although they seem to be the only majuscules that obviously try to imitate the details of the blackletter type. (Again, only a fresh and thorough survey would answer these questions, since they depend on matters of paleographical interpretation).

- 2) It doesn't matter that some other manuscript majuscules seem to imitate the printed versions, because, for example, the "B" majuscules are spread out over the entire volume, and are not contained within the "B" alphabetical section, like "W" and "S" -- although, quite unhelpfully, these instances are not listed or cited.

- 3) According to their judgment, the "B" looks more like "period handwriting" and so may not be an imitation of the typography at all. (None of these terms are defined, nor is there an attempt here to explain the many and varied ways that typography and paleography interacted in the period).

- 4) Ergo, the annotator still must have had an attachment to the letters "W" and "S," despite any further evidence that might be discovered -- and of course those just happen to be the initials of William Shakespeare.

Biblical quotations

Occasionally the annotations are quotations from the bible -- Koppelman and Wechsler claim to have identified twelve such quotations, "and most of these are followed by short indications of chapter and verse" (33). (This raises a few questions: What is the relationship between cited and uncited phrases? Are phrases that are not cited as biblical -- such as the "Drought In Sommer" annotation discussed above -- really "biblical"? At least in the same way?). Koppelman and Wechsler state that the biblical quotations are closer to the language found in the Great Bible (1540) and the Bishops' Bible (1568), as opposed to the translation found in the Geneva Bible, which Shakespeare seems to have turned to around 1600 or so. However, they also state that most of these quotations are not exact transcriptions -- and thus that they must have been quoted from memory: the annotator "has essentially entered a memory from church into the margin" (33). This completely disregards the appropriative nature of early modern reading and commonplacing, but for reasons I will explain, I don't think that this is a crucial issue here.

Consider the case, mentioned above, of the line quoted from Psalm 71, line 21:

After comparing the translations of several different bibles, Koppelman and Wechsler conclude -- and rightly so -- that the wording of this annotation is closest to the psalm as printed in the Great Bible. As they state, quoting another scholar, "we can see how this example coincides with Peter Milward's findings, in Shakespeare's Religious Background, that 'when he uses the phraseology of the Psalms, it has been noted that Shakespeare follows the Great Bible, as used for the Psalms in the Book of Common Prayer'" (34).

I have two problems with this quotation: first, it should be noted that Milward's work is both personally and ideologically motivated: he is a Jesuit priest who has long advocated for a "Catholic Shakespeare," and you can about read this commitment, and the work which Shakespeare's Beehive cites, in his online autobiography.

Second, and far more importantly, the claim that Shakespeare imitated the phrasing of the Psalms from the Great Bible -- when he quoted the Psalms -- is absolutely correct. This is because everyone in England knew this textual version of the Psalms, due to a detail that is mentioned, but completely (and irresponsibly) passed over: this is the translation used in the Book of Common Prayer, the book that was found and used in every church in England, the book that was reprinted and bound with countless bibles for over a century, and the book that was still used, in some locations, in the Anglican church into the twentieth century. Biblical quotations -- and especially those taken from the Psalms -- thus cannot be used as evidence, in any way, for dating the annotations, or to demonstrate a kind of identifiably personal memory. This version of the Psalms was pervasive in early modern culture. (Thanks to Aaron Pratt for some expert advice on early modern biblical and textual culture).

So, yes, it is quite likely that this particular quotation -- and perhaps the others, as well, if they were subjected to similar analysis -- was written down from memory. This seems to be the case for the "Drought In Sommer" annotation, too -- the Great Bible and Bishops' Bible read "drouth in Sommer," while the Geneva reads "drought of summer." Neither is an exact match, but again, this phrase occurs in a Psalm, and thus would have been widely known. And the fact that it is not cited as a biblical quotation may mean that it is simply a remembered phrase, and not consciously marked as biblical.

What does this mean? Koppelman and Wechsler claim that the "faine" annotation "is surely a case of a personal memory of an incident from his [whose?] life coming to the surface through a word association and being thus recorded" (34). There are two problems here: 1) most people (and any pious person) in the period could have made the exact same association, and 2) the phrase that immediately precedes this quotation is as follows: "We do not find any use of this line in the works" (34). That is, in this particular case -- which seems to match (some of) the other biblical citations in the Alvearie -- one can only argue for some kind of personal investment in, or simply a memory of, the Psalms, and nothing more. They must abandon the methodology of finding parallels between the annotations and the works in this case. Whatever this tells us, it tells us nothing about Shakespeare.

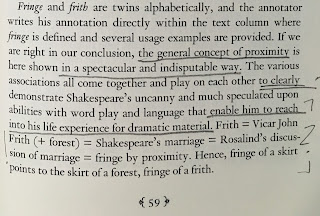

There is a further problem: as you can see from the image above, there are multiple colors of ink, meaning that "this annotation" -- or, rather, "these (three?) annotations" -- were not written at the same time, which includes the possibility that they were not written by the same person. At the very least, this should be considered three annotations, instead of one. Again, I have not done a complete survey of the biblical quotations, but it is possible, and likely, that one particular reader made this particular kind of connection between the Psalms and some of the terms listed in the dictionary. Koppelman and Wechsler do not mention the difference in inks in their analysis of this annotation, and it is difficult to determine from the digitized image exactly which marks are written in which inks. They do show that the first phrase -- "We are faine to vse" -- is probably taken from Baret's preface to the letter "A" (although they do not mention the French translation that appears just beneath this phrase). The phrase does occur in the preface to "A" and it is underlined there, which may indicate a progression for this cross-reference. Someone has also written a capital letter "A" next to the phrase and its translation. The second phrase, "I was faine to seeke," seems to be in a different ink, and it may be taken from the preface "To the Reader" where, again, this phrase is underlined. (Someone clearly read this book with care). Koppelman and Wechsler then go on to identify a three line passage from Much Ado About Nothing in which the words "faine," "seeke," and "vse" all appear. (Gopnik, who is by turns gently credulous and gently skeptical, finds the idea of a connection here "a little far-fetched").

The chapter on "personal markers" continues by drawing attention to some very specious stories that have been told about Shakespeare. They claim that "it would be disingenuous" not to mention an annotation which quotes Psalm 46: next to the entry for "knappish" (as explained in the entry, a variant for "knavish") an annotator has written "he knappeth the speare in sunder." It is not cited as biblical, but "knappeth" is the word used in Great Bible (and thus the Book of Common Prayer), although it was altered to "cutteth" starting with the Geneva Bible. It is also yet another instance in which a word omitted from the dictionary is inserted at the appropriate alphabetical place.

This leads Koppelman and Wechsler to recount unreliable stories, such as the possibility that poets were hired to help write the King James (i.e. the Authorized) version of the bible (1611), and that Shakespeare may have written the version of Psalm 46 that appears there, due to a numerological coincidence involving the words "shake" and "spear." This is the kind of conspiratorial speculation popular in mystery novels, and they state that they are not "leaning heavily on the 46th Psalm as a reason for our final hypothesis" -- in part, I believe, because this exact phrase does not appear in Shakespeare's works. However, they do say that

"as observers and recorders of the evidence, we would be coy to shy away from certain annotations, or pretend that these will not be noticed once the magnifying glass is handed over from us to everyone else" (40).This is a rhetorical tactic that Shakespeare's Beehive uses very often:

- 1) Koppelman and Wechsler claim to be merely disinterested, neutral "observers" whose only goal is to present any "evidence" which might be relevant -- or, in this case, "evidence" that they seem to fear that certain other people will notice, and who (perhaps?) may respond with an accusation that they have not been comprehensive or forthright.

- 2) Here as elsewhere, they refer to the most basic bibliographical fact: this annotation exists, and is a phrase found in Psalm 46. The fact that it exists is not in question; the fact that it is a quotation is likely. This does not prove anything.

- 3) Considering the theories about what some people have "discovered" in the Authorized Version -- theories that are not found in mainstream scholarship -- there may be a Shakespearean interest in Psalm 46. To be more explicit, based on the story they have just recounted, a claim exists that Shakespeare wrote this version of Psalm 46 -- a claim that they do not explicitly endorse, but which they do state is "still a debatable topic."

- 4) A conclusion is reached that is vague enough to maintain plausible deniability -- that is, they raise an issue, and get very close to implying that it may be true, without fully committing. Then a further conclusion is reached that seems to be either circular or illogical. In this case (starting with a big "if") :

"If our annotator did participate in the KJB translation of the 46th Psalm, he obviously then was already familiar with the Bishops' Bible version and would seem to have chosen to retain the word cutteth from the Geneva Bible in place of the Bishops' Bible's knappeth" (40)Let me parse this sentence in order to draw out what it is implying:

- "If our annotator did participate in the KJB translation of the 46th Psalm" = if poets were ever involved with this translation (even though there is no evidence presented here that poets ever were, beyond the speculative interpretation of Psalm 46) then it is possible that "our annotator" -- who has been previously identified as the poet William Shakespeare -- may have been involved.

- "he obviously then was already familiar with the Bishops' Bible version" = the version of this phrase in the Bishops' Bible is the same as that found in the Book of Common Prayer, and so most people would be familiar with it; however, since they have previously claimed a specific connection between the annotator's memory of the Psalms, and the annotations, without any attention to the Book of Common Prayer, some (but not all) of which may have some connection to Shakespeare's works, then he is still plausibly the annotator.

- "and would seem to have chosen to retain the word cutteth from the Geneva Bible" = the word choice follows the Geneva version, rather than the older versions which they have just argued Shakespeare (or "the annotator") had a particular connection to; but, as Koppelman and Wechsler state at the beginning of the chapter, the Geneva version of the bible is what Shakespeare seems to have worked with after 1600 or so, and the Authorized Version was not published until 1611; so the verbal discrepancy that would seem to invalidate the earlier line of reasoning is explained away with a new line of reasoning.